Basic HTML Version

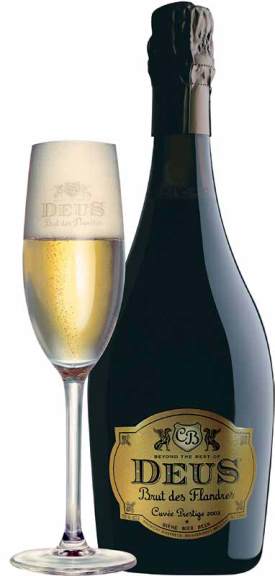

dominate the nose with fruity undertones of pear, sweet apple, and

lemon zest. DeuS has a honey-covered biscuit flavor with a dry finish

and powerful carbonation that compliments its slight alcohol warmth.

Usually, high alcohol beers like these can be kept for a few

years to develop their flavors. Aging DeuS will mellow out some

of the spiciness and develop a deeper fruit character. It is always

a matter of opinion, though I personally don’t recommend aging

bière bruts, as their spiciness helps enhance their powerful yet light

edge. Allowing that character to mellow would remove some of

the beer’s sparkle.

LETTING BEER GO

C

ellared beer is an unforgettable experience that can be

achieved by anyone willing to

wait years for the beer to mature.

Admittedly, the vast majority of beer

is not meant to age. Stale beer is

most associated with the compound

trans-2-nonenal, known for its wet-

paper aroma. While this particular

smell is unsavory, some oxidative

compounds can give the beer a

more complex, intriguing flavor,

developing sherry notes and a fruit

character that is unachievable through

normal fermentation.

How the beer is stored will

determine how the flavors develop as the

beer ages. Improper storage will produce

off flavors in beer in an unimaginably

quick time. Direct sunlight can cause a

skunky flavor in beer in less than a minute.

Beer is best kept in a cool, dark space. It

should be stored at cellar temperatures, or

below, somewhere between 45-55 degrees

Fahrenheit. Unlike wine, beer is meant to

be aged upright. The cork does not work favorably with the flavor of

beer and should not be in contact with the liquid.

Strong beers like barleywines and Belgian ales are the most

commonly aged beers. As you explore high end beer bars, their cellars

will contain a trove of aged oddities such as a ‘99 JW Lees Harvest Ale,

a strong English brew that is commonly aged for a decade or more.

Upon drinking this 15-year-old beer, one notices that its spicy, earthen

hop character left a long time ago. What remains is a strong

ale with honey nectar and juicy plum flavors accenting

a warming brandy character. Many beer enthusiasts will

travel across country or even the world to seek out these

rarities, always hunting for the next dusty bottle hidden

in the cellar of a bar.

The higher alcohol content in strong ales make

them more resistant to the oxidation reactions than stale

beer. There are a few exceptions, however, as a general

guideline a beer should have at least seven-percent ABV

(alcohol by volume) if it is going to be aged. One of

the exceptions is if the beer contains live yeast. In the

bottle, these active microorganisms will consume

oxygen and other compounds that stale the flavor

of beer. Brettanomyces and other microorganisms

that accompany wildly fermented brews like

lambic are slow-acting and can allow the beer

to be aged for decades.

THE WILD SIDE

OF BEER

I

n a regular brewery, the brewer goes

through painstaking efforts to ensure

that only the intended yeast is in the

beer. Any other yeast or microorganism

is considered wild and can result in an

infected beer. Enter lambic.

While normal brewers are trying to

winter

|

spr ing

131

RARE

BEERS