Basic HTML Version

40

winter

|

spr ing

And, choosing among the private guides, our favorite is a particularly

resourceful man who has written two books on the events of those days

(“Arnhem 1944,” “Omaha Beach”), and lectures at the British Royal

Military Staff College (equivalent to the U.S. Army War College): the

witty, often acerbic, but always informative guide,

Colonel

(Retired)

Oliver Warman

.

With a name like Warman, it is no surprise that after a 30-year

military career in Her Majesty’s Service as a Special Forces officer –

machine gun and parachutist divisions – the colonel would spend his

retirement overseeing the construction of a new museum near Pegasus

Bridge, delivering speeches to the Staff College, and guiding civilians and

soldiers through European (the Somme, the Ardennes, Calais, Dunkirk,

Antwerp, Alsace Lorraine, the Eagles Nest, Berlin, Crete, Anzio, Monte

Cassino) and North African (Tunisia) World War Two battle sites.

We were made aware of Colonel Warman by a Montecito couple

–

Jane

and

Bruce Defnet

– who had already experienced the Colonel’s

guide abilities. Upon exchanging e-mail, we arranged for a two-day private

tour, using our vehicle (which turned out to be an extremely efficient –

45-50 miles-per-gallon – Mercedes A180 diesel rented from Hertz).

The story of the landings is the stuff of legend: the uncertainty of

the weather; construction of plywood and inflatable “dummy” military

vehicles and ships for a fictional First United States Army Group (FUSAG

of Operation Quicksilver) further down the coast built to fool the Germans

into believing the landings would take place elsewhere (at Pas de Calais)

or at least lead them to believe the Normandy landings were a feint and

that the real landing at Calais had yet to occur; assemblage of the largest

fleet of ships, boats, landing craft, and water borne vessels in the history

of the world; the “impregnable” Atlantic Wall brimming with minefields,

underwater obstructions, machine gun and artillery nests, guarded by

seasoned German soldiers led by Hitler’s best general, Field Marshal Erwin

Rommel (“The Desert Fox”). Arrayed against him were the best the Allies

had: Montgomery, Patton, Bradley, and Eisenhower. It was a clash of titans.

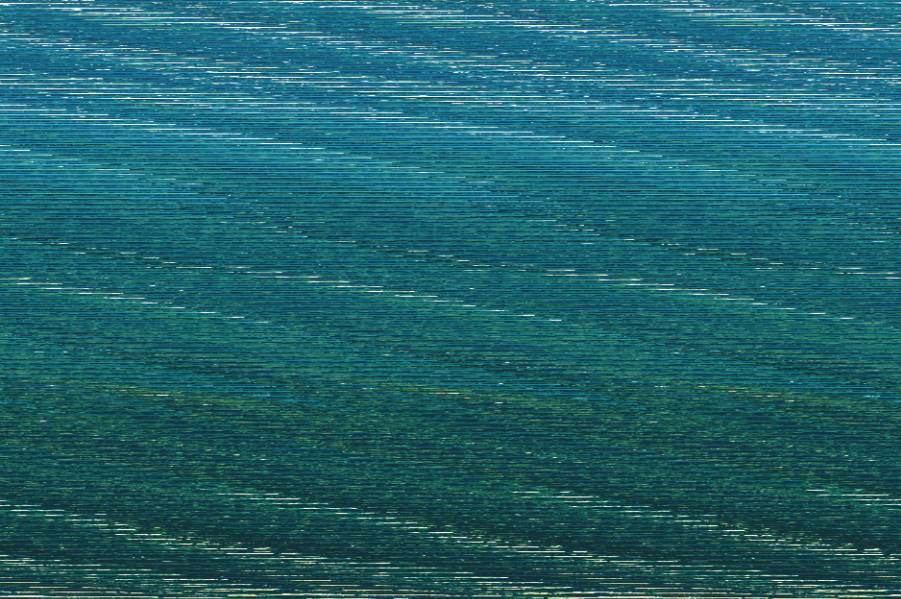

This “castle” in Creuilly, not far inland from the

Normandy landing beaches was British Field

Marshal Montgomery’s headquarters. The window

on the central tower (below the flag) is where

Walter Cronkite, Edward R. Murrow, and other war

correspondents delivered their invasion reports.

Opposite (not in photo) is a manor where Monty

hosted a lunch for Winston Churchill, George

Marshall, and Dwight Eisenhower on June 8 1944,

just two days after the D-Day landing.

Now a five-star hotel, this estate is where German soldiers executed 68 Canadian

Prisoners of War. A young soldier asked the German commandant what he should do

with the Canadians they had taken prisoner and the commandant said simply, “Shoot

them.” The young lieutenant did that by taking ten men at a time, placing them against

a garden wall (not seen, but to the right) and shooting them. All 68 were buried in

shallow graves. When Canadians retook the building, they saw 68 pair of boots

sticking out of the ground under the wall. Upon learning what had happened as they

removed the dirt and realized that 68 of their compatriots had been killed execution

style, rumor has it they made a decision to not take any prisoners.

Twelve years ago, a plaque that had been placed directly on the wall was removed

in the cause of “European unity,” and re-mounted on a different wall on the road

outside the nearby town.

D-Day